To the Scratch

A scratch. A mark or line drawn to signify a starting place.

Tuesday, November 4, 2014

The Story of Water is the Story of Us

This is the Ohio River, taken from Little Hocking, Ohio facing the bottomlands of West Virginia. What can't be seen through the morning fog is DuPont's Washington Works plant, which sits directly across the river. Also invisible are the molecules of PFOA--a long-lived, synthetic processing aide used, for example, in the production of water- and grease-repellant consumer goods. For more than fifty years, DuPont released PFOA-laced waste into the river and into the bloodstreams of those living on its watershed.

From the essay, On Confluence. Written for the Science and Environmental Network and the 2014 Minneapolis Women's Congress on the Rights of Future Generations.

Sunday, October 12, 2014

The Homes We Drove Past

Wednesday, October 8, 2014

When the Raspberries Come

"Until I had children, I had been out of touch with cycles and seasons, disconnected from the ecological system of which I am a part. But since I’d become a mother, I’d grown into the habit of juxtaposing our lives with the lifecycle of our raspberries. They had become timekeepers, steady and sure during the disordered days of early motherhood."

Monday, April 28, 2014

The Whole Is Greater than the Sum of Its Parts

|

| Rear rail entrance to Union Carbide's former Bound Brook, NJ plant Taken with Dad, May 2013 |

"Before I was born, before he married my mother, my father made polystyrene plastic.

His plant could manufacturer 8000 pounds of polystryene in an hour, 60 million pounds in a year. Every plastic pellet he or anyone ever made is still with us."

June 2014

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

Thoughts on Home and Place

On Arlington, Massachusetts

The Place Where You Live | Orion Magazine

February 3, 2014

Our block ends in an access trail to ten acres of hilltop conservation land bounded by densely built neighborhoods. The summit, called Mount Gilboa since the 1700s, marks the edge of the Boston basin—a glacier-carved rim that overlooks the flatlands stretching toward the harbor. It took three attempts to put this land into conservation. The first proposal failed in the 1880s.

From this vantage, one is awed not by the expansiveness of the land, but by the intensity of its use and repurposing, by the possibility of what it once looked like in the days of the Massachusett. To the north, a landfill, once a market farm, is now a playground. To the east, winding through the grid of rooftops, is a defunct rail corridor now bike path. In the distance, the high-rises of Boston, the fanning cables of the 8-laned Zakim Bridge, the aging stacks of the Mystic Generating Station, and everything in between, the landscape through which at least a couple million people pass daily.

But it was in this sequestered patch of urban wild that I first felt my place in the geological and human continuum—even though I am, like many here, a transplant. I walked these rocks regularly, before motherhood, following the meandering stonewalls that marked some once meaningful boundary. And while pregnant, I waded through snow so thick my knees bumped against my belly with each plunging stride. I wandered its rings of networked trails, while one son toddled behind with lichen-covered twigs and sassafras leaves, and another clung to my back. But our favorite spot is a lean-to built on Gilboa Rock from fallen branches—maybe oak, maybe hickory. We rarely encounter others up here, so we imagine its origins and who must have come here before us. My sons dart in and out of the structure, shoring it up with found sticks. The welcomed wind mutes the sirens below on Massachusetts Avenue, and the ancient rocks ground us after a too-rowdy birthday party and a morning wasted on television.

But it was in this sequestered patch of urban wild that I first felt my place in the geological and human continuum—even though I am, like many here, a transplant. I walked these rocks regularly, before motherhood, following the meandering stonewalls that marked some once meaningful boundary. And while pregnant, I waded through snow so thick my knees bumped against my belly with each plunging stride. I wandered its rings of networked trails, while one son toddled behind with lichen-covered twigs and sassafras leaves, and another clung to my back. But our favorite spot is a lean-to built on Gilboa Rock from fallen branches—maybe oak, maybe hickory. We rarely encounter others up here, so we imagine its origins and who must have come here before us. My sons dart in and out of the structure, shoring it up with found sticks. The welcomed wind mutes the sirens below on Massachusetts Avenue, and the ancient rocks ground us after a too-rowdy birthday party and a morning wasted on television.

Link here: The Place Where You Live -- Orion Magazine

Sunday, February 9, 2014

"The Broken-Hearted Hallelujah"

From Kathleen Dean Moore, a compelling call for more "broken hearted hallelujahs":

|

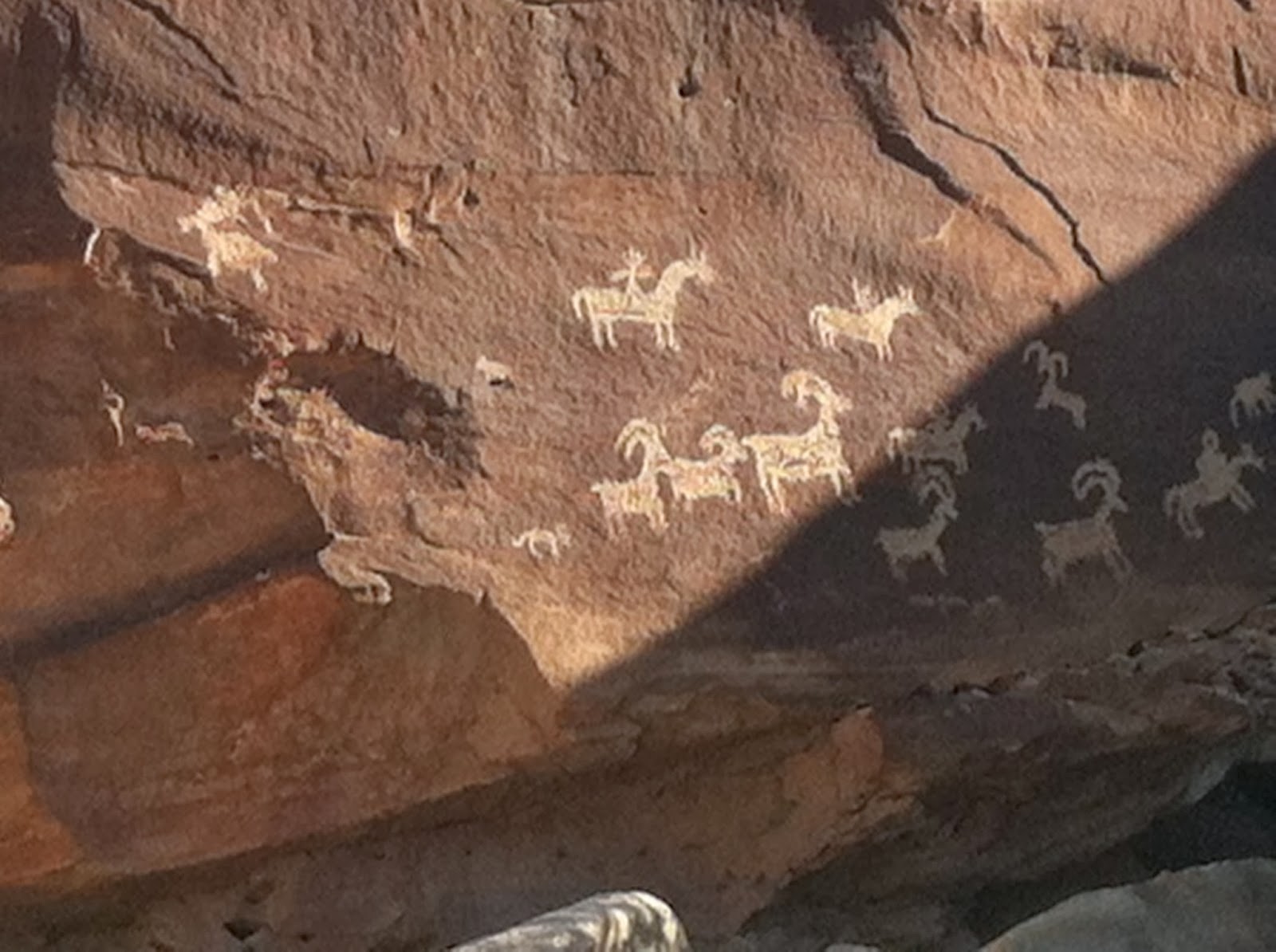

| Arches National Park, Moab, Utah (2013) |

"As the true fury of global warming begins to kick in—forests flash to ashes, storms tear away coastal villages, cities swelter in record-breaking heat, drought singes the Southwest, the Arctic melts—we come face to face with the full meaning of the environmental emergency: If climate change continues unchecked, scientists tell us, the world’s life-support systems will be irretrievably damaged by the time our children reach middle-age. The need for action is urgent and unprecedented.We here issue a call to writers, who have been given the gift of powerful voices that can change the world. For the sake of all the plants and animals on the planet, for the sake of inter-generational justice, for the sake of the children, we call on writers to set aside their ordinary work and step up to do the work of the moment, which is to stop the reckless and profligate fossil fuel economy that is causing climate chaos.Some kinds of writing are morally impossible in a state of emergency: Anything written solely for tenure. Anything written solely for promotion. Any solipsistic project. Anything, in short, that isn’t the most significant use of a writer’s life and talents. Otherwise, how could it ever be forgiven by the ones who follow us, who will expect us finally to have escaped the narrow self-interest of our economy and our age?"

|

| Arches National Park Moab, Utah (2013) |

My response: "On What We Bury"

ISLE (Winter 2014)

"We slip behind a sandstone dome, smooth like a church bell, and sit on the edge of the rim, its walls striated, and each striation a chapter in its history. To look down into the canyon is to look back through time. My friends lie with their bodies sinking into the contours of the warm, rust-colored rock. I drop to my knees. We do not speak. The tourists murmur. Two ravens call. The wind chants through the canyon below. I unfold the pamphlet the ranger handed us when we entered the park. It explains how everything we see was once buried beneath an ocean, and how the ocean deposited the sand and salt that surrounds us now as exposed sandstone, as red rock. Is there a more humbling experience—kneeling in a desert where an ocean rose and receded, and where humans have roamed for 10,000 years?"

|

| Arches National Park, Moab, Utah (2013) |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Friday, January 13, 2012

Hope is a Thing with Feathers

My second column went up at Odewire.com last week. On hope. And birds. Among other topics.

He reminds them that reawakening our senses, often dulled by the details of our lives, enables us to experience the thrum and throb of life and seasons and cycles. And it is our keen awareness of elemental life that grounds us in hope, that delivers us moments of grace in an oft times gritty world.

Update (January 2015): Since Odewire.com discontinued its fantastic blog, I have archived a cached version of the essay here."We humans are only beginning to understand that life is more than a sum of its parts, that we are more than the sum of our parts. We are learning that any one part of a complex system connects to every other part, and that the interaction of multiple elements creates complex chains of influence that we may never anticipate.When we reach beyond ourselves, maybe, just maybe, we set in motion something that will resonate through those tied to us in ways we might not foresee."

Reach beyond yourself

Individual actions matter in ways we might not anticipate.

Environmental sociologists and psychologists who observe our responses to the growing awareness of environmental problems are finding that we live in isolation too often. Too often, we keep what we know private, rarely speaking to one another candidly about what concerns us. How do we live with what we know? Well, according to social scientists, what we need are more routine opportunities to convene and converse about issues like climate change, and to lay plans for a different future together.

Their findings also hint that our individual actions matter in ways we might not anticipate. Sociologist Kari Norgaard learned from her study of how people in one community spoke about climate change that neighbors and community influence how we live. They shape how we respond to what we know and our capacity to see purpose and to find hope in what we can do. Our connections, her findings suggest, matter deeply to our resolve to reconcile the tensions between what we know and how we live.

In November 2011 independent filmmaker Sophie Windsor Clive and her colleague Liberty Smith posted a stunning two minute clip titled Murmuration. Maybe you’ve seen it? Chances are you have. The video went viral.

]The first time I watched it, I didn’t know that a murmuration is a flock of starlings. Nor did I know that starlings, at dusk, somewhere near the winter solstice, swarm into a stunning, swirling cloud of mystifyingly ordered chaos.

Clive and Smith’s video elicited from me pure, biological joy. My heart rate quickened, almost as if it sought synchronicity with the shifting undulations of the starling formations. I felt calm, yet breathless, weeping from the wonder of it. Sharing the experience with Clive and Smith, despite mediated through a computer screen, elicited tears from the same place in me that wept at the birth of my sons, that weeps at the feel of their breath on my neck as I carry them to bed. It is a mix of awe and gratitude for bearing witness to all that is mysterious and complex and miraculous about life.

Scott Russell Sanders, in his book Hunting for Hope: A Father’s Journey (Beacon Press, 1999), writes that wonder and hope are intimately tied. Hunting for Hope is Sanders’ mediation on how he lives in hope. It is a gift he offered to his children, to their generation, and to his students, all of whom have asked him “haltingly, earnestly,” in one way or another, how he confronts despair, how he lives with what he knows, how he would advise them to live, given all they now know, too, through him, about the troubled world they will inherit.

He reminds them that reawakening our senses, often dulled by the details of our lives, enables us to experience the thrum and throb of life and seasons and cycles. And it is our keen awareness of elemental life that grounds us in hope, that delivers us moments of grace in an oft times gritty world.

That the murmuration video went viral, to me, speaks volumes about this particular moment in which we live. It speaks to what we yearn for.

The more I’ve learned about starlings since seeing that video, the more I’ve come to realize how little we truly understand the dynamics of ordered chaos, how little we understand what motivates and coordinates the birds to fly as they do. As I learned from Brendan Keim’s reporting on Wired.com, scientists understand that each bird is influenced by how the birds immediately adjacent to it moves, such that each bird seeks to mimic the motion and speed of those around it.

But the collective, interactional dynamics, it seems, remain a mystery. How is it that a flock of starlings, whether 100 or 1000, know to turn or adjust speed in unison, as if one? Their bodies somatically know something about how each individual connects to a system, how a system influences each individual. They know how a part connects to the whole, and how the whole influences the parts. They know about criticality and tipping points.

Watching the shifting cloud of starlings was, for me, much like Sanders describes: a wellspring of hope that life is, as it always has been, mysterious and extraordinary, teacher and exemplar, worth honoring and savoring.

But their movement also offered me hope in the form of metaphor, too, for we humans are only beginning to understand that life is more than a sum of its parts, that we are more than the sum of our parts. We are learning that any one part of a complex system connects to every other part, and that the interaction of multiple elements creates complex chains of influence that we may never anticipate.

When we reach beyond ourselves, maybe, just maybe, we set in motion something that will resonate through those tied to us in ways we might not foresee.

That is as hopeful a thought as I can imagine.

Happy New Year.

By Rebecca Altman

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)